In recent years, the Android malware landscape has become increasingly dynamic, with new threats exploiting sophisticated methods to target less vigilant users. I was thrilled to read the recent report by CTM360 about the PlayPraetor trojan. It’s incredible that this malware has infected more than 11,000 Android devices via fake sites and ads on social platforms. It reminded me of a malicious app I was investigating, suspected of containing a variant of the infamous GoldDigger malware.

PlayPraetor is a prime example of how modern Android malware has learned to mix classic social engineering techniques with advanced features such as abuse of accessibility services, keylogging, and screen capturing. In the same way, GoldDigger also uses these mechanisms to steal banking credentials, OTPs, and sensitive information.

In this article, I’m thrilled to present a simple analysis of a suspicious APK using MobSF, JADX, and Ghidra. This analysis will showcase some simple practical steps for recognizing infection indicators and gaining a deeper understanding of the inner workings of Android banking malware.

What is GoldDigger?

First identified by cybersecurity firm Group‑IB, GoldDigger is a sophisticated Android banking trojan that emerged in mid-2023, initially targeting users in Vietnam. It gained notoriety for attacking more than 50 financial, e-wallet, and cryptocurrency apps. Distribution campaigns used fake websites impersonating trusted sources like Google Play, telecom companies, and local government services.

Key characteristics of GoldDigger include:

- Abuse of Accessibility Services to capture screen content, simulate touches, and extract sensitive information.

- Interception of SMS messages, allowing attackers to bypass two-factor authentication (2FA).

- Use of Virbox Protector, a commercial obfuscation tool, making it harder to analyze and detect.

- Multilingual support, including Vietnamese, Spanish, and Traditional Chinese, suggesting expansion beyond Vietnam.

- Modular design: Later versions (like GoldDiggerPlus) include components such as GoldKefu, enabling overlay phishing and real-time voice phishing (vishing) via fake customer service calls.

These features place GoldDigger in the same threat category as PlayPraetor: both are adaptive, stealthy Android malware families that combine technical sophistication with social engineering to steal financial data and gain full control over infected devices.

Static Analysis

To explore this further, I ran a sample APK, suspected to be related to GoldDigger/Gigabud. Using tools like MobSF, JADX, and Ghidra, I aimed to uncover static indicators of compromise and behaviors typically associated with sophisticated mobile malware.

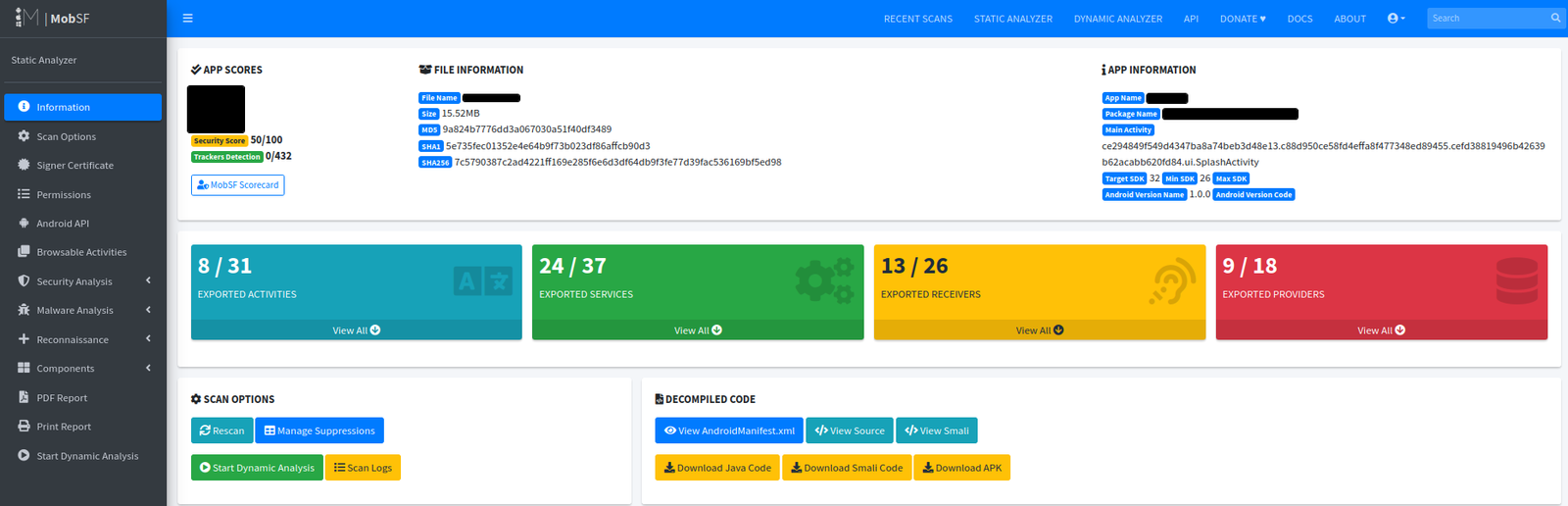

The first step was MobSF, which provided a high-level overview of the APK. The tool immediately raised red flags:

- Security score: 50/100

- 24 exported services

- 13 exported broadcast receivers

- 9 exported content providers

This level of component exposure is highly unusual in legitimate apps and is often seen in trojans that want to be invoked externally or remotely. From this alone, the APK already looked suspicious and worth deeper investigation.

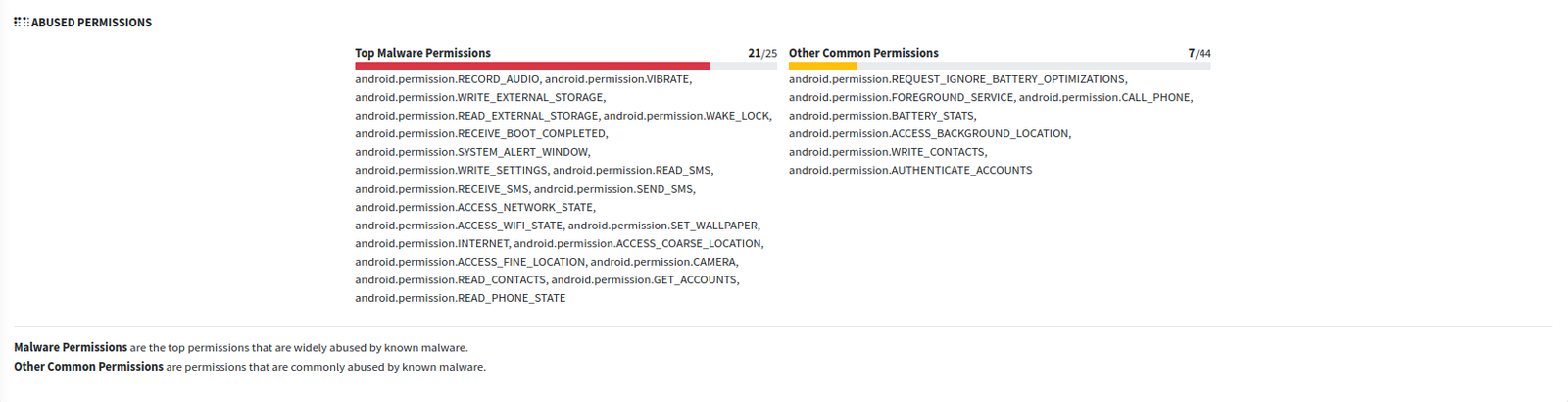

MobSF also revealed that the app requested 21 out of the 25 permissions most commonly abused by Android malware. Some of the more concerning ones include:

- RECORD_AUDIO — Used to capture conversations

- READ_SMS — For intercepting OTPs and messages

- READ_PHONE_STATE — To access device identifiers and call state

- ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION — For GPS tracking

- READ_CONTACTS — To harvest contacts for social engineering

The permission set alone is a strong indicator that the app is designed to operate with high levels of surveillance and control — consistent with banking trojans.

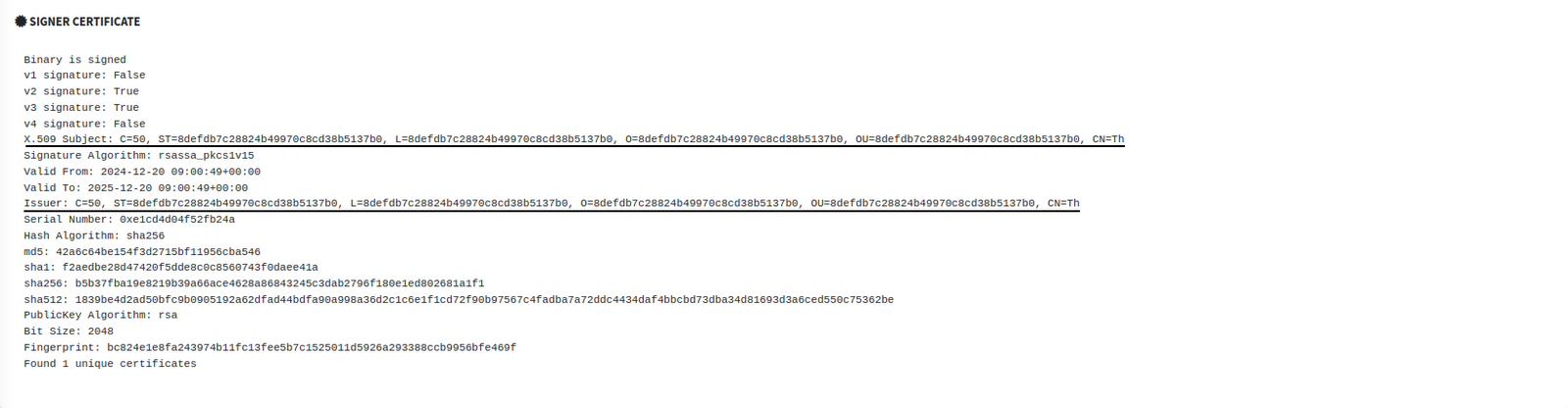

Next, I examined the APK’s signing certificate. It was self-signed and valid for just one year, another strong indicator of malicious intent. This short certificate lifespan allows attackers to frequently repackage and rotate malware samples, helping them evade signature-based detection. Legitimate applications, by contrast, are typically signed with long-term certificates issued by trusted authorities.

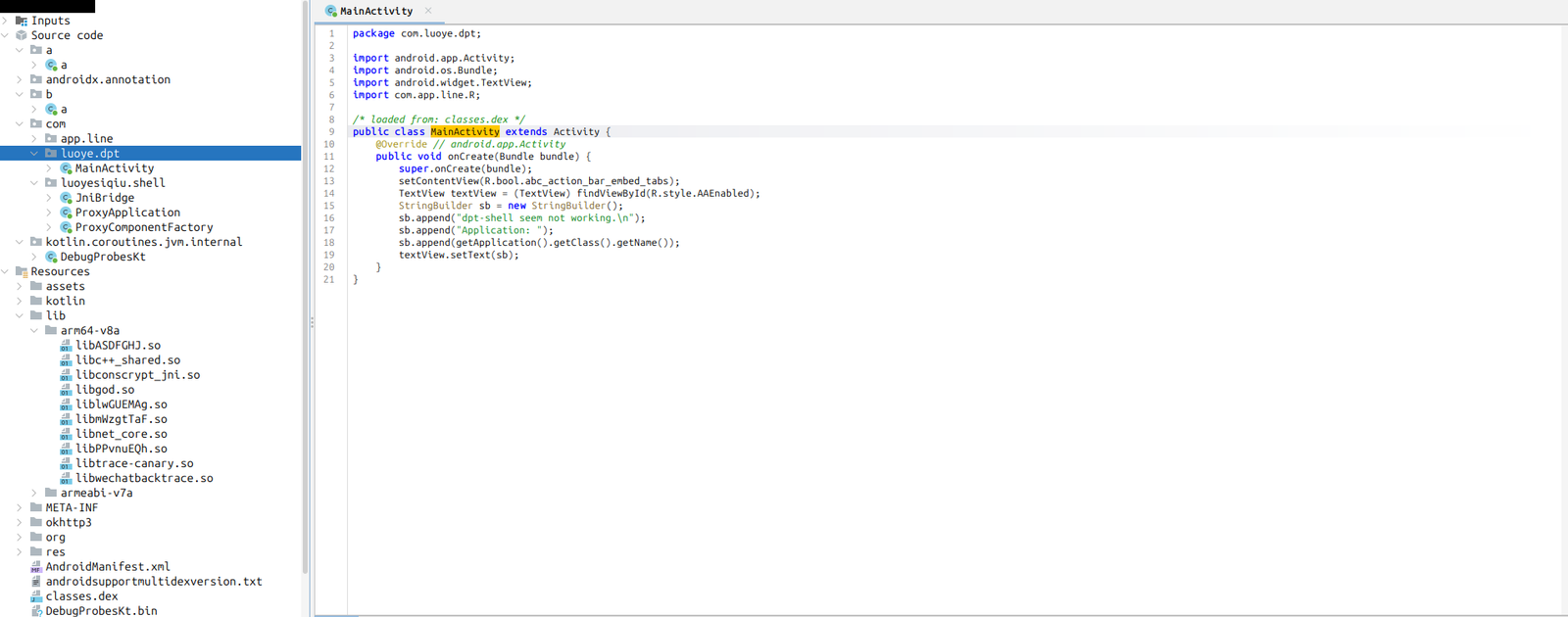

During decompilation with JADX, the app’s main Java code appeared minimal or almost empty. This is because the APK relies heavily on native libraries (likely written in C/C++) to store and execute its core malicious logic.

These native components often use techniques like dynamic code loading and encryption (for example, through packers such as dpt-shell) to hide the real payload from static analysis tools. By shifting critical functionality into native code and loading it only at runtime, the malware effectively evades reverse engineering and detection.

This approach is common among advanced Android banking trojans to increase stealth and make analysis significantly more challenging.

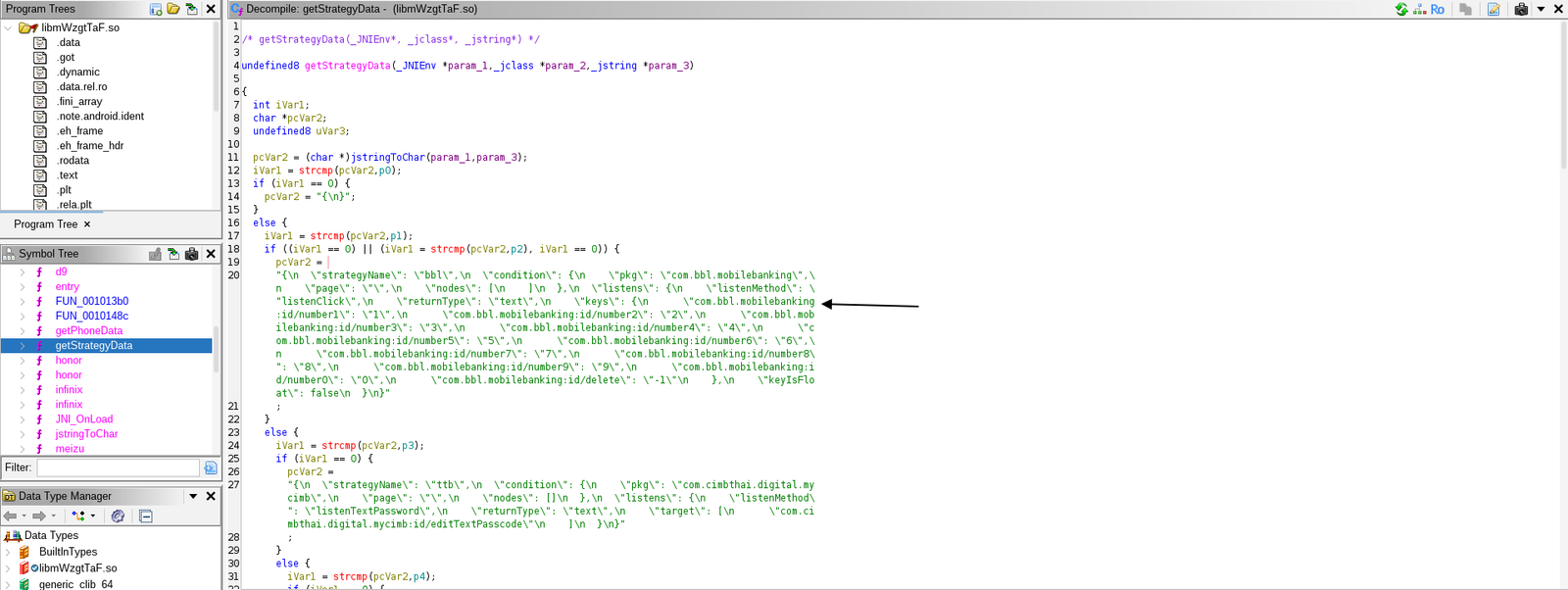

To further analyze the embedded native code, I loaded the app’s .so library into Ghidra. There, I discovered a method named getStrategyData, containing hardcoded strings referencing financial apps such as:

- com.bbl.mobilebanking

- com.cimbthai.digital.mycimb

This points to a modular architecture, where the malware activates specific logic depending on which apps are installed. This technique is used in GoldDiggerPlus, allowing the malware to adapt dynamically to its environment and target specific financial services.

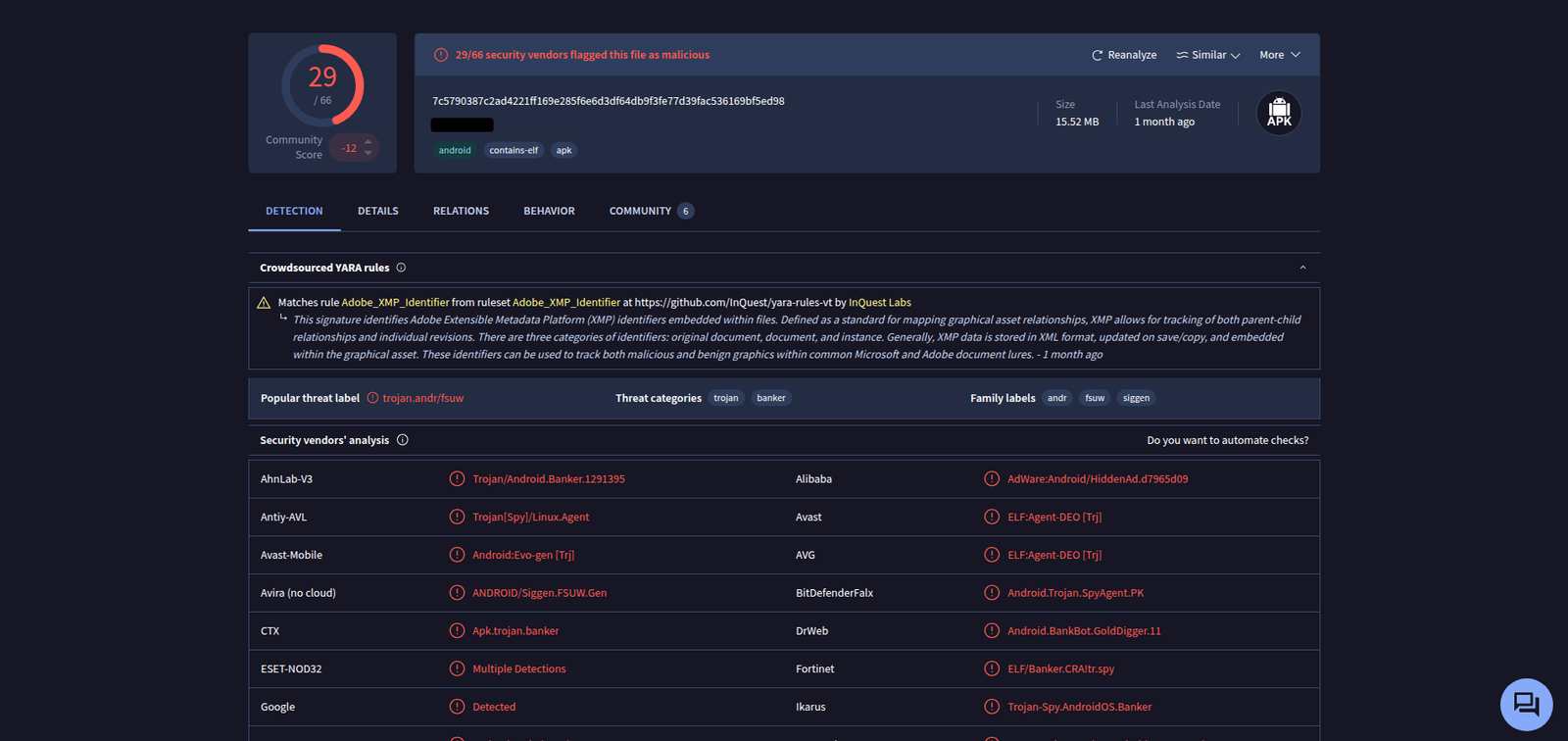

Finally, I scanned the sample on VirusTotal, where it was detected by 29 out of 66 antivirus engines. Common labels included:

- Trojan.Android.Banker

- Spy.AndroidOS.Banker

- Android.BankBot.GoldDigger

These detections confirm that the APK is widely recognized as malicious and possibly a variant of the GoldDigger family.

Conclusion

Through this hands-on analysis of a suspicious APK resembling GoldDigger/Gigabud, we’ve seen how powerful and evasive modern Android trojans have become. By combining technical tricks, social deception, and legitimate system permissions, attackers can compromise devices with minimal user interaction.

Thankfully, tools like that make it possible, even for solo analysts or small teams, to dissect and understand these threats. The goal of this article is to encourage more proactive analysis, security awareness, and a deeper appreciation for the mechanics behind mobile malware.